The meadows of Pahalgam, long held in the embrace of conifers and silence, now carry an uneasy echo not of the streams that once sang joyously through the valleys, but of an abrupt violence that struck when no one expected it. The terror attack on tourists shook the very soul of Kashmir’s fragile hospitality sector, reminding all once again that beneath its breathtaking beauty, the Valley continues to wrestle with a haunting tension.

In the weeks following the tragedy, the air in Kashmir has become heavier, not just with grief, but with questions about safety, about resilience and about the future of its lifeline: tourism. For years, this region has worn its beauty like armor, believing that its snow-capped peaks, emerald meadows, and serene lakes could disarm even the most hardened hearts. But when violence returns as it did that day in Pahalgam the illusion splinters and the wounds reopen.

The impact wasn’t just physical or political; it was deeply emotional. Hoteliers, shikara owners, pony riders and handicraft vendors many of whom have known only tourism as their source of livelihood found themselves grappling not only with sorrow for the victims, but also fear for what might come next. A sudden silence settled over places that had only recently begun to hum with the music of languages from distant lands. Streets that buzzed with the chatter of visitors and the bargaining of tourists turned contemplative. People walked slower. Shops closed earlier. And the hopeful wait for summer crowds turned into an anxious glance toward the empty hills.

The truth is, Kashmir has always lived in contradiction an eternal tug-of-war between nature’s generosity and history’s cruelty. Each season, the Valley opens its arms to guests who come seeking peace, healing and a communion with beauty. And each time, the shadow of conflict threatens to dim that welcome. Yet the people here with hearts hardened by experience and softened by culture have always found ways to rise. They have rebuilt burnt homes, reopened shuttered shops and repainted fading signboards that promise tea, saffron and the ever-hopeful “Kashmir is safe.”

This latest attack, however, was not just a blow to business. It pierced the trust between host and guest, that fragile yet powerful relationship that has long sustained Kashmir’s image as a land of warmth and hospitality. The shock of seeing tourists symbols of friendship and curiosity caught in violence unsettled not just the visitors but the very community that prides itself on its mehmaan-nawazi. For many Kashmiris, it felt like a personal affront, a betrayal of the unwritten code that guests are sacred.

The days that followed were painted in a palette of conflicting emotions. Anger, fear, sorrow and helplessness coexisted. There were prayers in mosques and temples alike, candles lit in memory and a collective sense of mourning that transcended the usual divisions. The Valley seemed to hold its breath, as if hoping that silence could somehow undo the horror. And in that silence, the memories of older tragedies came rushing back other attacks, other seasons, other disruptions to the dream of normalcy.

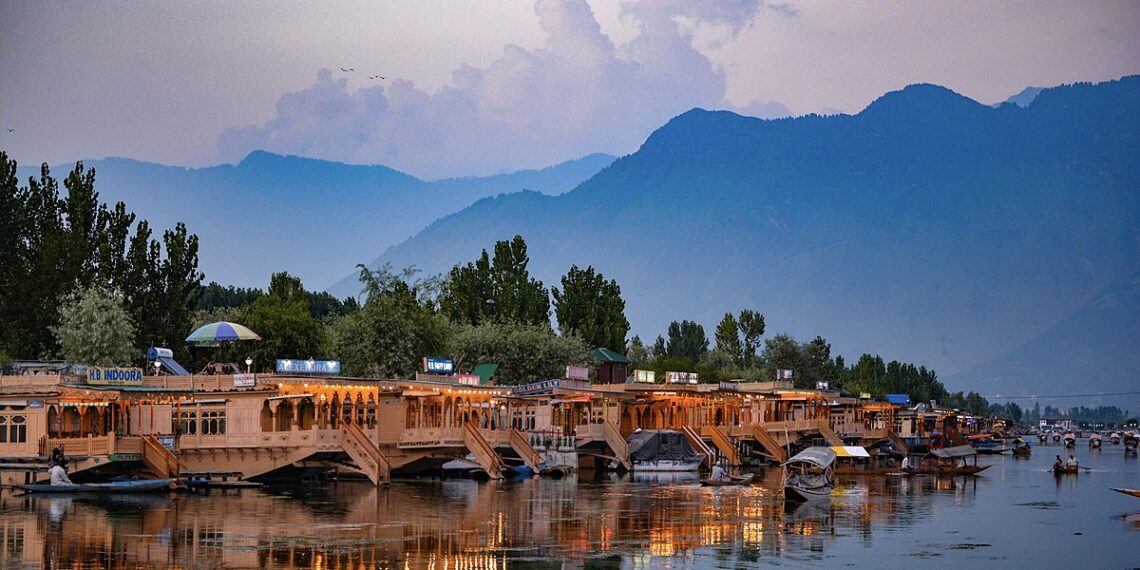

Yet even amidst the pain, life stirred in quiet defiance. On Dal Lake, a few shikaras still ventured out, their owners smiling a little more nervously than before. In the gardens of Srinagar, children chased kites under a slightly more watchful sky. And in Pahalgam itself, a few families returned, not to vacation, but to reclaim routine opening guesthouses, brushing dust off counters and placing flowers on windowsills as if to say: we will not let fear win.

For the outsider, it might seem perplexing this resilience, this determination to move forward. But to understand Kashmir is to understand that survival here is not a luxury, it is a practice. A daily decision. Every morning, the people of the Valley choose life over despair, work over idleness, hope over fear. It is not naivety. It is necessity. And tourism, fragile though it may be had always been both the mirror and engine of that resilience.

There is a certain choreography to the tourist season in Kashmir. The spring begins with tentative steps a few early visitors, charmed by almond blossoms and cool breezes. Then comes summer, with its caravans of explorers, newlyweds, filmmakers and families. The local economy dances to their rhythm: guides dust off their stories, drivers wash their cars to a gleam, artisans stitch and carve with fresh zeal and houseboats are prepared like brides. One attack does not erase this rhythm but it disrupts it. It breaks the tempo. And the dancers pause, uncertain whether the music will resume.

Conversations now are tinged with worry. Will people still come? Will the cancellations continue? What about the Amarnath Yatra? What message will this send to the outside world? These are not just questions of economy, but of identity. For many Kashmiris, welcoming guests is not merely work it is pride. It is how they engage with the world, how they tell their story. Losing tourists feels like losing a voice.

But even in the wake of violence, there are flickers of resistance not through arms, but through acts of kindness. Stories began circulating of local Kashmiris rushing to help the victims, transporting the injured, offering shelter and speaking out against the attack with unflinching clarity. These gestures may never make headlines, but they form the quiet backbone of the Valley’s dignity. They are reminders that for every act of terror, there are hundreds of acts of humanity. And it is these small lights that guide the Valley forward.

The government’s response the debates in television studios, the politics around tourism and terror all of that continues in the background. But on the ground, in the narrow lanes of Anantnag, the open courtyards of Pahalgam, the floating markets of Srinagar, the real effort is not in words, but in action. It is in the reopening of shops, the cleaning of hiking trails, the rehearsals of Bhand Pather performers who still hope for audiences. It is in the smile of a hotel owner who says, “Aap aaye, yahi kaafi hai” you came and that’s enough.

Kashmir does not forget. But it forgives in strange ways by carrying on. By tending to its gardens, by serving kehwa to strangers, by painting wooden signs that read “Welcome.” And so, even after this attack, the Valley will prepare once more for the next season. The tulips will bloom again. The Lidder will continue to rush through Pahalgam’s heart. And slowly, perhaps hesitantly, footsteps of tourists will return lighter, more cautious, but present.

To visit Kashmir now, after the Pahalgam attack, is not just a journey for leisure. It becomes a quiet act of solidarity. An affirmation that beauty deserves to be seen and that fear should not decide the fate of dreams. Those who return will not find a region untouched by pain, but they will find a people determined to offer love despite it.

And that, perhaps is the enduring message of tourism in Kashmir that even in its darkest hours, the Valley refuses to be defined by violence. It insists on beauty. On hospitality. On connection. And in doing so, it reminds us all that peace is not a gift bestowed from above, but something forged daily through smiles, shared meals, open doors and the courage to move forward.