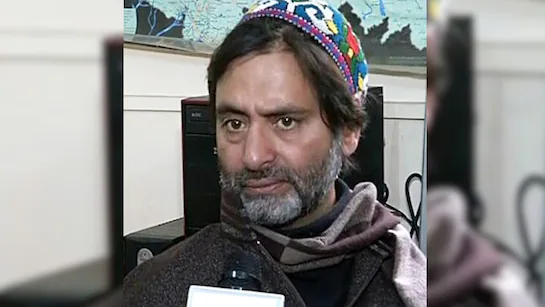

The winter of 1990 still hangs in memory like a permanent frost. Streets emptied overnight. Locks clanged on wooden doors that had been left without goodbyes. And in the middle of it all stood Yasin Malik — young, defiant, loud — the man who, along with his band of JKLF militants, helped turn neighbours into fugitives.

A Valley on Edge

Malik did not act alone. The entire landscape of Kashmir was shifting by the late ’80s. Guns were crossing the Line of Control, slogans echoed in crowded mohallas, and fear seemed to seep into every conversation. The JKLF, with Malik at its centre, gave militancy a face and a voice. To some, he was the rebel daring New Delhi. To others, he was simply the man who made life unlivable.

And then came the night when the whispers became a roar. Pandit families remember it vividly: posters slapped on walls, threats scrawled on paper, loudspeakers carrying messages that felt more like ultimatums than slogans. The choice was simple and cruel — leave or risk death.

Leaving Everything Behind

They left in buses, trucks, on foot if nothing else was available. Habba Kadal, Rainawari, Sopore — whole neighbourhoods emptied in weeks. Families carried a few blankets, some jewellery, maybe a stack of exam notes. Everything else — homes, temples, friendships — was abandoned.

Ask those who fled and they will tell you: the violence wasn’t abstract. It had names and faces. Killings of prominent Pandits made sure the warnings weren’t taken lightly. Malik and his comrades in JKLF created the atmosphere where one killing was enough to send ten families packing. Multiply that by hundreds, and you have the exodus.

A Cultural Amputation

What did Kashmir lose that winter? More than statistics can explain. The sound of temple bells in downtown Srinagar went silent. Neighbours who had shared noon chai for decades were gone without farewells. Kashmiriyat — that overused word about coexistence — cracked open under the weight of fear.

Malik, meanwhile, found his footing in politics. Strange, isn’t it? That the same man who oversaw those days of terror would later sit across tables speaking of “peace” and “dialogue.” Pandits in exile found it insulting, even grotesque. How could the man who watched them flee claim to speak of reconciliation?

The Double Image

It worked, for a while. Malik’s transformation from gunman to “Gandhian” was celebrated abroad. Cameras loved him. Diplomats shook his hand. But for Kashmiris who lived through 1990, this was theatre. The wounds of exile cannot be patched over by press conferences.

And when the courts finally caught up — with charges of terror financing, with his conviction — the facade fell apart. The law saw what ordinary Kashmiris had always known: Malik was no peacemaker. He was a man whose politics thrived on other people’s pain.

The Memory That Endures

More than thirty years have passed. Pandit families are scattered across India, some still nursing the hope of return, others resigned to permanent exile. Yet the memory of who drove them out, who created the fear, who stood to benefit — that hasn’t faded.

Yasin Malik’s legacy in the Valley isn’t of leadership or courage. It is of betrayal. He stole neighbours, fractured trust, and left the Valley poorer — culturally, socially, spiritually.

And the truth is stubborn: long after Malik’s name is forgotten in speeches and headlines, the cold winter nights of 1990 will still be remembered in Kashmiri homes as the time when one man’s politics helped turn a community into refugees.

(Hailing from Kashmir and based in New Delhi, Mehak Farooq is a journalist specialising in defence and strategic affairs. Her work spans security, geopolitics, veterans’ welfare, foreign policy, and the evolving challenges of national and regional stability.)